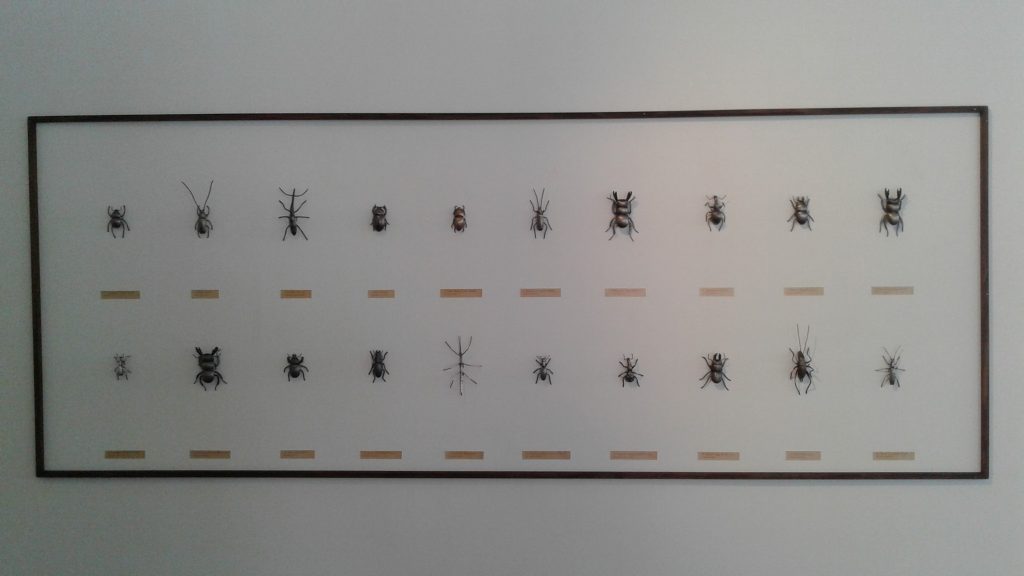

Moth brooches

Silver Brooch.

Eyrewell Beetle

Holcaspis Brevicula

Status; extinct

Only ten Eyrewell beetles have ever been found. No more will be found, as their habitat of kanuka and exotic pine trees has been replaced by 14,000 cows, at the behest of Ngai Tahu, in a dairy conversion that happened in 2019. DoC attempted to work with the owners of the land to ensure some protections for the small black carabid beetle, but were ignored. Unfortunately our conservation laws do not extend to private property, unless the endangered flora or fauna at risk is protected under the Wildlife Act.

The Eyrewell beetle was threatened from the outset, when it’s kanuka habitat was destroyed to make way for exotic pine plantations, the eponymous Eyrewell Forest. It survived on to exist in 7000 hectares of pine, but when the pine forest was returned to Ngai Tahu in 2000, the beginning of the beetles’ obituary was written.

Small, black, flightless, and un-charismatic, the beetle had no chance of prevailing when pitted against the prospect of income generated from the sale of milk powder and infant formula, grown off the back of a center pivot irrigation system, fed by the Waimakariri River, in a traditionally dry region of Canterbury.

The Eyrewell beetle was about 1 cm long, shiny black, nocturnal, and couldn’t fly, though it could run, but not fast enough to outrun the shredders that chipped the pine trees up into sawdust so fine any creature larger than a pinhead could not survive. It’s tenacity that ensured survival of it’s earlier habitat destruction could not survive this final blow.

Three Kings Click Beetle Brooch, silver

Helms Stag Beetle Brooch, silver

Huhu Beetle Brooch, silver

Giraffe Weevil Brooch, silver

Giraffe Beetle.

Lasiorhynchus barbicornus.

Tuwhaipapa

The male giraffe beetle is the longest New Zealand beetle, at 85mm, the females are half that size.

They have been accused of not being a true weevil, because they lack an ‘elbow’ in their antennae, but it’s just a slur; they belong to the sub-family Brentinae.

They are found commonly in the lowland forests of the North Island, though they have been found as far south as Greymouth. I am dismayed I have never seen one, as they are active during the day, and they shelter quietly in the tree canopy at night, feeding on sap. If disturbed they will drop suddenly to the leaf litter, and feign death for up to an hour, which is a long time for a beetle who only lives for two weeks, though the larvae live for a couple of years.

The sexual dimorphism is pronounced between the males and females. The males are much larger, and can fly. They have a much longer rostrum, or stiff snout, and the antennae are located at the end of it. The females are smaller, flightless, and their antennae are halfway down their rostrum, which leaves the end of their snouts free for drilling into dead tree bark in order to lay eggs.

The males use their long rostrums for fighting over females, naturally enough. If a singleton male stumbles upon a happily mating pair he will rudely rake his mandibles on the male’s back, and worse still, attempt to dislodge him by pulling on his opponents legs with his mandibles. This is probably why many males are amputees.

Once the challenger has dragged his opponent off, they will fight each other with their elongated snouts for the affections of the female. Amusingly, while this show of shirt-fronting is happening, a smaller male will often sneak in and mate with the female in question, proving diminutive size is no barrier to successful mating.

Curiously, they have been found with colonies of mites living on them. It’s unknown whether the mites are parasitising the giraffe weevils, or hitching a ride in order to disperse more widely.